Russia is waging an information war in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region. DW Akademie is taking action and training journalists and media users in these regions how to deal with disinformation campaigns.

In many small towns like here in Borjomi,Georgia, people also watch Russian satellite TV. The local media markets are financially weak.

Tiraspol, July 2016. Tiraspol? Yes, you read it correctly. Tiraspol. That’s the capital of Transnistria, a tiny unrecognized territory wedged between Ukraine and Moldova that broke away from Moldova in 1990. Transnistria is home to some 500,000 inhabitants who are predominantly Russian speaking. It’s also home to one of the so-called “frozen conflicts” that Russia has fomented in the neighborhood.

The audience in Tiraspol attending the DW Akademie panel discussion on migration and refugees was an eclectic mix. Crowded into the venue belonging to an independent cultural association, one of DW’s cooperation partners, were journalists, teachers, students and two UN refugee agency representatives, as well as four official panelists sent by the government (or the country’s intelligence service).

The discussion revolved around migration and the risks resulting from the flood of refugees into Germany and other parts of Europe. Around whether it was true that Germany’s security situation had deteriorated since the arrival of the refugees, as is claimed by Russian media.

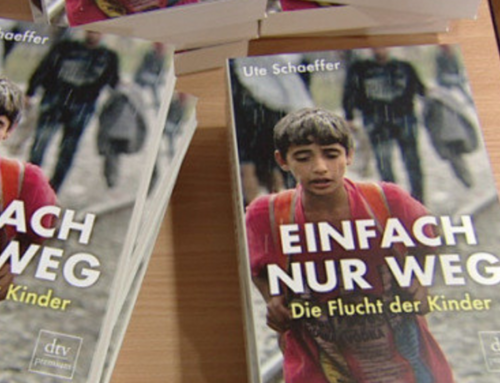

It was about the refugees’ own stories as recounted in the DW book I wrote about refugees called “Einfach Nur Weg” (which translates as “Just Get Away”). Most of all, the discussion was about the concrete steps of creating the book – about the interviewees and whether and how I conducted research.

Broadly speaking, the discussion was about the credibility of journalism and how journalists work. In Transnistria, as in other post-Soviet states, independent media is rare and people are regularly exposed to disinformation campaigns. At the DW Akademie event, it became clear how the Kremlin’s information war is playing out in the region – not just in pro-Russian Transnistria but also in other countries where DW Akademie is active, such as Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine and Moldova.

Military transports like this one in Georgia are part of everyday life in many post-Soviet countries due to frozen conflicts

It’s an unequal battle where glossy, wealthy media supported by rich Russian investors fight it out against financially weak and less professional media.

Georgia alone has around 140 TV stations and 70 radio stations competing for a share of the market and most of these outlets aren’t economically viable.

Moldova, with a population of 3.5 million, has 70 TV stations, 60 radio stations and 170 newspapers.

These countries don’t have independent media; instead, the media (alongside banks and the courts) has become a tool used by oligarchs to fight their power battles. In most of the post-Soviet countries, people’s trust in politics and the media is at an all-time low. The media in Moscow are quick to use this to their advantage, filling the vacuum with pro-Russian information.

The Kremlin’s strategic goal is to destabilize its neighborhood by destroying the credibility of state institutions and pro-Western politicians and undermining the growth of democracies. That’s why Moscow is feeding territorial conflicts in South Ossetia for example, as well as in Ukraine’s breakaway Donbass region and in Transnistria. The same motivation is behind Moscow’s (dis)information campaigns that use targeted messages and modern packaging to advertize its policies. And the distribution of these messages is easy – Russia’s neighboring states are home to large minority groups who speak better Russian than the official languages of the countries they live in; these minorities almost exclusively tune in to the free-to-air Russian programs.

In the non-linear, hybrid war that’s being waged to advance Russia’s national interests, the media play a key role. The first casualty of this war is truth. Among its victims are journalists and independent media companies as well as everyone else who’s trying to navigate the jungle of half-truths and biased, or blatantly false, information.

This is where DW Akademie comes in, with its focus on strengthening media literacy among tomorrow’s decision-makers. We specifically seek to train young people, civil society organizations, teachers and university professors. First and foremost, media literacy means asking the right questions and developing a critical approach to the media. What distinguishes fact from opinion? How can I find alternate information? The overall goal is to strengthen the basic human right to freedom of information. For Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region, this means equipping civil society, media users and media professional with the appropriate tools to keep a cool head under fire in the information war, distinguish fact from fiction and realize the importance of, and use, research and facts.